A while back, I wrote an article on the camera in the Apple Macbook Pro A1398 lid assembly. In that article, I published the pinout of the FaceTime camera in the lid, and demonstrated how it could be wired directly to USB and function as a generic USB webcam – but not a very cheap one, since the panel assemblies are still pretty expensive.

Well, it turns out that you can buy the bare camera module for a very reasonable $5 at everybody’s favorite auction site. A visitor to this site wanted to use these cameras in a standalone application and offered to send me one to play with, in return for a little bit of investigative work. Sounds like fun, let’s take a look.

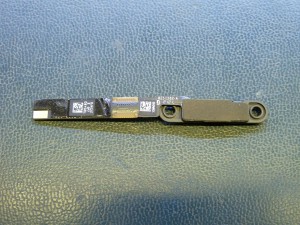

As a recap from last time, note that this module contains not only the camera but also the laptop’s ambient light sensor (seen at left on the front view). There is a little foam ring around the ALS to prevent errant readings caused by the LCD backlight or the camera activity light. Next to the right is the camera lens, and the white circle is the activity light. The camera sensor and the ALS are on a little flex PCB which is soldered to the rigid board containing the rest of the circuitry. Many of Apple’s other assemblies are made as a single rigid-flex assembly, but the two cameras I’ve investigated have both had separate control and sensor sub-boards. I wonder if the camera assemblies would otherwise be damaged in reflow.

The top of the control board houses a VIMICRO VC0358SMMB. We can assume that this is similar to the VIMICRO VC0358PQNB, for which there is a public data brief (PDF), but this part is in a wafer-level BGA package instead of LQFP. The suggested SPI memory is probably present as the 6-pin device to the lower right, and presumably contains the USB descriptors identifying this part as a FaceTime camera. The other WLCSP to the left looks suspiciously like some sort of voltage regulator, though I didn’t bother to measure the nearby capacitor voltages to verify that. Note that although the VC0358 has microphone input capability, this board does not appear to contain a microphone.

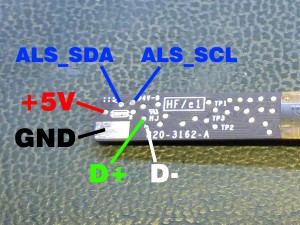

The input connector is on the righthand side of the board as seen in the front view. The connector is a 6-pin, 0.4mm-pitch FFC receiver. I probed around the board and determined the pinout of the connector to be the same as it is on the motherboard side of the harness (pin 1 is marked with an arrow):

| Pin | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | GND | USB/ALS Ground |

| 2 | D+ | USB Data Positive |

| 3 | D- | USB Data Negative |

| 4 | +5V | USB/ALS Voltage In (+5V) |

| 5 | ALS_SCL | Ambient Light Sensor I2C Clock |

| 6 | ALS_SDA | Ambient Light Sensor I2C Data |

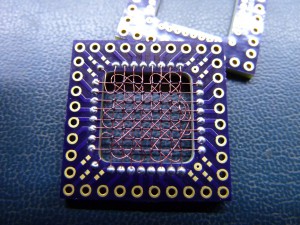

This is all well and good, but soldering to the 0.4mm connector is an absolute nightmare. It’s not something the average person is going to want to attempt. We could buy a little FFC jumper to plug in, but if we only paid $5 for the camera, having to buy more parts would negate that cheapness. Thankfully, if we remove the sticker from the rear of the module, the manufacturer has left us plenty of testpoints. I mapped the ones that connect to the connector pins, and came up with the following pinout:

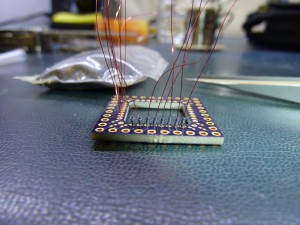

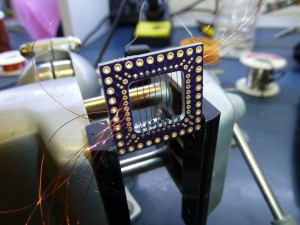

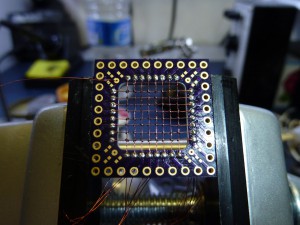

Using this scheme, I soldered on an old cut-off USB cable:

And what do you know, as soon as it was plugged in the camera was recognized the same way it was in the previous post – as a USB Composite device containing two FaceTime HD Camera devices. Again, as last time, one of the two devices has no available driver, but the camera works just fine with only one of its sub-devices installed:

The camera takes a selfie. It’s a bit blurry, possibly because it can’t properly focus at this range. I didn’t notice that when I was taking the photo, oops.

So there you go. If you need a cheap and small USB camera for something, these are pretty easy to hack onto. Hopefully this is useful to somebody!